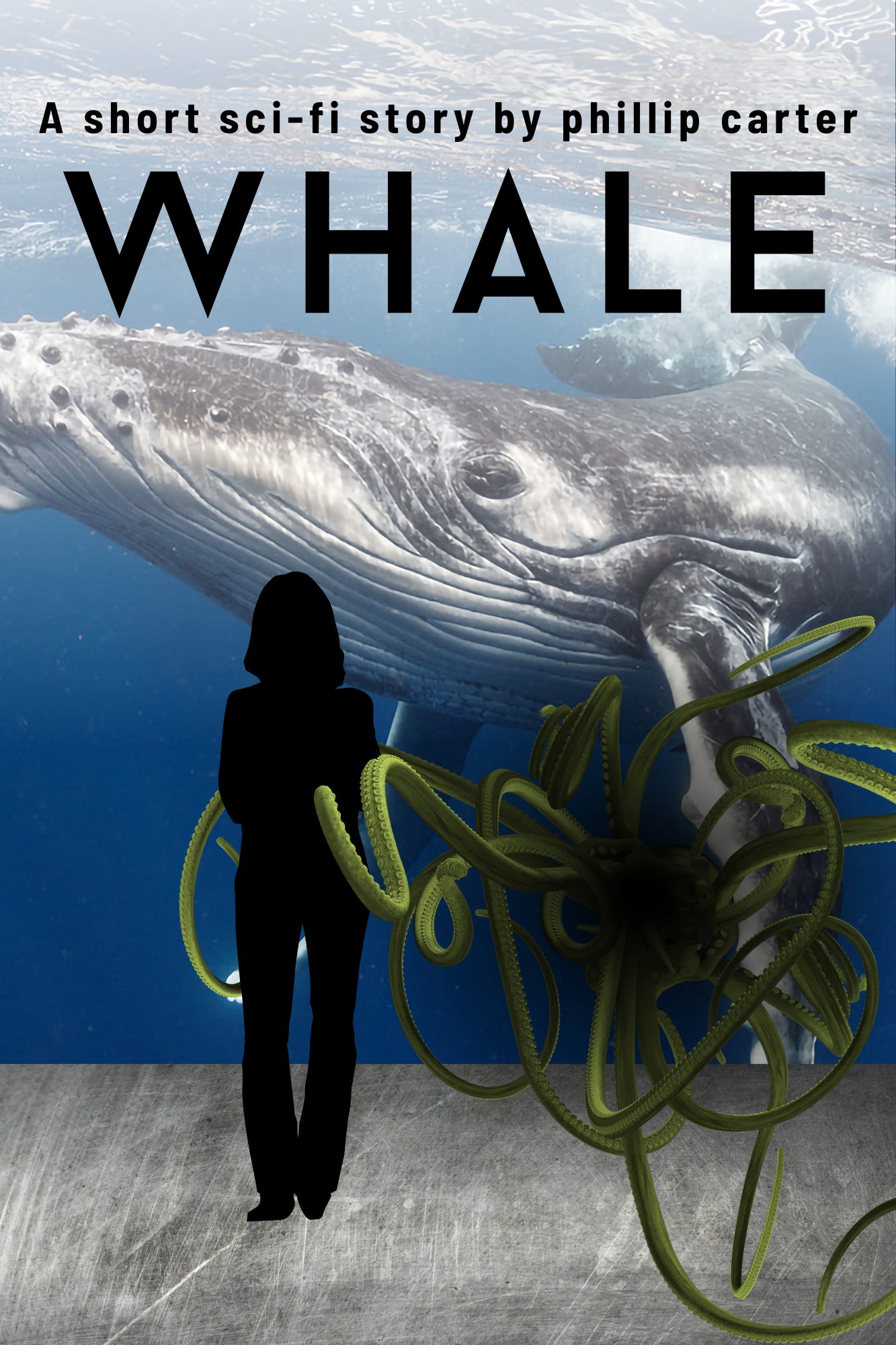

Short story - WHALE - part 3

If you missed the other parts, there's a link in this email.

If you missed the other parts, don’t worry, just click the buttons below.

Here’s some background music, before we begin.

WHALE - part 3

When she woke up, Galina Agafonov was terrified. She was shaking and cold, her body still convinced she was dying out in space. And when this feeling subsided, it was soon replaced by abject horror. Of course, they had taken precautions so as not to frighten her, creating a humanoid android to introduce her to their world, but it was not enough. Galina had barely noticed the android, instead staring at her hands, and patting down her legs. The hospital gown was cool to the touch. Everything was too perfect. There was not a scar on her body.

“My crew,” her voice faltered. She turned to the android. It was silent and uncaring.

“My ship. What happened to my ship?”

There was no reply.

“Where am I?”

Again, no reply. The android was not designed to lie. The room was comprised of white panels. The wall opposite Galina’s bed featured one way glass. Galina turned again to the android, shook her head, then faced the glass.

“Speak to me,” she said. I remember my legs being crushed. What was that? Coldbed hallucination? Dreamscreen meltdown? Or has something else happened?”

Her thoughts lingered on a silent third possibility. She felt an unease that crept up her spine, right where her memory chip used to rest. She began piecing together an idea.

“I died?” she asked finally, turning to the android. “You brought me back?”

The android did not reply.

“This is the future?” her attention returned to the glass. The question made her uncomfortable as it lingered in the air. If she was wrong about her theory, then she had just failed any psychological assessment put upon her. She was deluded. If she was right, everyone she knew might be long dead.

She noticed a subtle movement to her right. The android was nodding to her question.

“H-How far?” her voice quivered. The android stepped to one side, speaking in a calm, deep voice. “You will discuss this soon. First, I must inform you that we have not yet found the remains of your crew.”

Galina’s lips moved almost imperceptibly. An unspoken word lingered and faded. A hot pressure built up behind her eyes. Her neck tensed, and she wanted desperately to beat this emotionless doctor to death. Surely in this future, whenever it was, they could bring the crew back just as they had brought her back. But there was something wrong. The heart monitor was beating just a little too monotonously. The plug sockets in the room were contemporary. If this was the future, things should have changed. Increasingly Galina felt that something was fake about the place. There was something missing in the air.

“This isn’t real. It’s a dreamscreen.”

“Close,” the android said. Finally, it had a glint in its eye.

“You have passed our tests. I believe you are ready to see me now.”

“Tests?” Galina asked. Before she finished speaking, something deep below the room clunked and whirred. The walls were lifted from the floor and split into pieces, drifting away into racks and compartments. Galina watched reality unfold. When the transformation was complete, she became aware that she was sitting in an enormous underground cavern, the ceiling pocked with greenish lights and glass corridors, the air filled with rails and girders and small flying machines. Before she could take it in she noticed another oddity. A spiralling door ahead whirred open, and something massive and indescribable spilled out of it. The android turned its attention to Galina, its eyes suddenly filled with life. Galina looked at it as the strange shape approached them.

“My name is Umvonk,” the android said. Somehow Galina knew the human before her was not real, that they were a mouthpiece for the thing approaching. The thing barrelled toward Galina, but she was not scared. She could not afford to be. Automatically, almost subconsciously, Galina had already established a firm grip on the metal stand of her heart monitor and was ready to use it as a weapon. The android had not noticed and had therefore been added to Galina’s list of potential weapons. She could use him as a shield, and if he had a pen in his pocket, could use that to gouge and stab her way out of this place.

But despite everything, Galina was smiling.

“Aliens,” she said to herself. The creature ahead slowed down now, coming close enough that she could see detail. Umvonk was comprised of hundreds of black tendrils of varying length, each marbled with lime colouration, each tipped with a lime green barb or hook. He stopped just ahead of Galina, moving some of his tendrils into an impression of a humanoid face with large, bushy, tentacled eyebrows.

“I am sorry about your crew.” The tendril face frowned. The android beside Galina was the one speaking again, Umvonk was miming. Galina relaxed her grip on the heart monitor, slowly crawling out of the hospital bed. She stumbled.

“What happened to them?”

“We don’t know. Should we find them in similar conditions to yourself, we intend to revive them also. But your fossil was nearly complete, found in several pieces, the largest of which was used to bring you back. You must understand that despite our technology, we cannot turn pulverised remains back into living beings. We cannot reanimate dust.”

“I understand,” Galina said quietly. She stood up straight and faced the alien. He sensed she was disappointed.

“You were a challenge; a micrometeorite had obliterated your brain.”

Galina considered what Umvonk had said, then asked him, “You called me a fossil. How long was I gone?”

“Ten million years,” the android said. Umvonk relaxed his tendril face into a neutral expression. A layering of green barbs became even bushier eyebrows, and another became a humanoid moustache. Galina found herself grappling with the huge expanse of time. Not only would her son be dead, but her whole species might have faded in that time.

But they hadn’t. This creature, Umvonk, was speaking perfect Russian.

“And my brain was obliterated?”

“There was enough, from the microchip recordings in your suit and the signatures in your brain, to put you back together.”

“Signatures?”

“Energy signatures. Our technology is more sophisticated than yours. There will be time to explain later.”

“But you can’t be certain this is the real me, can you?”

“This is as close as we will get.”

“There will be parts missing,” Galina said.

“Not much,” Umvonk replied. He relaxed from his human impression, the giant face of tendrils collapsing into a writhing mass that looked more like multiple warring creatures than one. Through the mess Galina almost saw the core of the thing, but it was mostly obscured by rapid movement.

“You’re beautiful,” she said.

“Always the scientist. Thank you,” Umvonk remarked. He smiled, three of his tentacle-faces forming a large arch that was froglike in appearance. He beckoned for Galina to follow him, and she began walking again with little effort.

“Brilliant,” Umvonk said, “Your new body functions perfectly.”

“It’s the same one, gosh, you even got my flat feet.”

“We were very thorough in reconstruction, though I must admit that this is a private project, a private museum,” Umvonk explained.

“I see,” Galina said.

“A large body of our archaeological work is unknown to the wider galaxy. Our projects, yourself included, are very vulnerable.”

Umvonk took Galina down a stone stairwell into another cave. This one was lined with a tremendous glass wall, beyond which was a glowing turquoise ocean. Deep within the water Galina could make out the distant shadows of towers and bulbous research stations embedded in the ocean, their orange domes gleaming and glistening with the flickering of signal lamps. Around these structures, giant sea snakes and strange arthropods moved and picked at bits of coral. Galina squinted, and for a moment wondered if she saw one of the arthropod things wielding a basic spear made from coral.

There were also whale-like creatures, each with humble eyes and a gloomy, aged expression. Their skin was a mottled white and grey, and their fins looked similar to the webbed feet of ducks. Galina was fascinated with them.

“Where are we now? Where is this place?” she asked.

“We are not too far away from Earth. We are still in the same ‘arm’ of the Milky Way galaxy, as humans called it.”

“Sorry, I meant this place in relation to your world. What is its purpose?”

“It is where we manage the evolution of this planet. This solar system, and several others unknown to the general population, are places where we vow to keep life protected from environmental factors beyond its control.”

“You prevent extinction,” Galina summarised.

“Essentially.”

“And that’s why I’m here.”

“Correct. You are free to leave, of course, whenever you wish,” Umvonk said. “But you are vulnerable, and there will be precautions. Nonetheless I can assure you, you are not stuck here.”

“I understand,” Galina said.

“I would like to learn about your life,” Umvonk continued, “This museum purchased your fossil from a treasure hunter and trader. He does not know we can bring fossils like yours back to life, not many do, so when you leave this world, you may wish to assume another identity. It may be wise for us to lose contact, for your safety, so I would like to learn all I can from you now, if you don’t mind.”

“I thought you brought me back using my brain?” Galina asked.

“We did. But we did not interfere with it beyond physical and energy-based reconstruction. We saw some memories, but not all. And personalities, ‘souls’ as you humans once called them, are things we cannot seem to find when picking through physical brains.”

“I see,” Galina said. She cracked her fingers and ran her hands through her hair. It felt the same as it always had. Soon a burning question surfaced within her as they watched the whales and the arthropods and the strange machines out in the murky ocean beyond the glass wall.

“Why would I need to assume another identity? Has something happened to humans? Are we hunted?”

Umvonk shook several composite heads.

“Keen archaeologists sometimes dress up as the things they are studying, as a hobby. They will recognise each other, there are certain irregularities, but you are pure human.”

“But there are other humans about as well, surely?”

There was silence.

“So the species ended. And you revived me. I can’t be the first, can I?” Galina asked. One of the whales had drifted close to the glass wall now. Galina could see the individual scales upon its body and the sleepy look in its eyes. Umvonk rolled and lolloped closer to Galina. She looked closely at him and noticed that some of his black-lime tendrils had fur or whiskers. She wondered if he was mammalian. Then, if perhaps he used these whiskers to pick up on vibrations in the air. All of these questions would be answered in time, for now she had more pressing questions to ask.

“I’m the first, aren’t I?”

“You are,” Umvonk said. “Galina Agafonov, you are the first living member of your species in at least seven million of those ten million years since your death. The species you belong to went extinct; the human race changed.”

“What happened?”

“A series of catastrophes that I believe it would be unwise to tell you about immediately. You are still stressed from waking up.”

“No, I’m not.”

“You are,” Umvonk said, “I can sense it.”

Umvonk was correct of course. Galina knew now that he was a walking bundle of sensory and communicative organs. He knew everything about her. He knew her heartrate, her body temperature, her mood. She thought about her son, about his first day at school and the day of their tearful farewell at the launch station. She wondered if Umvonk was aware of this too, if he could feel a mother’s grief echoing through her flesh. Her son was dead. There was nothing she could do to change it. There was no way to go back and make his life any better in those final, pathetically small years. Even if he lived a century or more, his life was less than a flicker of light in the eons that had passed between his birth and today. Galina felt her knees go weak, felt her stomach turn at the thought of him growing up without his mother.

She remembered him, remembered a promise to take him to a newly built aquarium upon her return. She remembered her college friends and her professors and her lovers. She remembered doctors and therapists and everyone she had ever despised. All of these people were dead, dust or less, scattered to space.

She imagined the Earth as a scattered mess of broken rocks now. Because the only way no other humans would be salvageable in this distant future was if something terrible had happened to Earth, perhaps her entire solar system. She turned to Umvonk slowly, trying to reabsorb the reality before her.

“I went to an aquarium when I was a child. With my mum and dad. There was a pod where you could stand inside a bent piece of glass and look out at the fish from underneath them. I spent over an hour there as other families came and went. It was so peaceful. I had my headphones on and couldn’t hear a thing from outside, just the music and the imagined noises of the colourful fish and sharks and crabs that moved around in there. It was so beautiful. Years later I told the crew of my ship, the Pallas, that that was the precise moment in my life in which I knew my purpose, in which I had a purpose. That was when I decided I wanted to be an astrobiologist. It was predetermined from then onward. I wouldn’t let that dream go,” Galina said. She was crying softly, trying to keep it from Umvonk, despite not knowing if he knew what crying was. She put her hands against the glass and watched as a smaller whale sidled up close to the other side, pressing its flipper against it, mimicking her.

“I told my son I’d take him to some new aquarium. I can’t even remember the name of the place now. He wanted to be a biologist too.”

“I know,” Umvonk said. “I have watched what remains of your ship records. I thought it was poetic that the first human to be resurrected would be you.”

“Why?” Galina asked. For the second time in ten million years, she reached up and brushed her hair back, then feeling it, wondering now how it felt as if it had been recently conditioned.

“You even copied my hair care routine,” she said, smelling a strand of blonde hair between thumb and forefinger.

“All on the ship records. All to make you as real, and as comfortable, as possible.”

“But why is it poetic that I’m here and nobody else. Why not the rest of my crew? What makes me special?”

Umvonk puppeted several of his tendrils into a kind expression and smiled reassuringly. He raised a tentacled eyebrow. Galina turned to the grey-skinned whale against the glass, pressed both hands against it. The whale replied by pressing a bony fin against the other side and blinking slowly. Galina absorbed the image of the whale. It was distinctly alien, but something about it was familiar, as if all life on all worlds would eventually discover the same limited set of almost perfect forms for each environment. In the background, two of the arthropods waged a difficult battle atop a service lift for one of the submerged cities.

Galina made eye contact with the whale. She wondered if sharks, which had predated humans, might have outlived them. She reimagined Earth now as something more complete than cosmic wreckage. Perhaps runaway climate change, war, or an interstellar invasion or asteroid had wiped out the humans. Perhaps they went the way of the dinosaurs. Perhaps it was quick and merciful. Perhaps her son had grown old and happy, knowing his mother sacrificed herself for the betterment of their species, and he died believing that same species would carry on long after him, stretching into the last days of the universe as it now might.

She did not break eye contact with the whale, remembering how she had once looked at a shark this way as an undergraduate. She felt like that undergraduate again, asking heavy questions and nervously expecting an answer she didn’t want and wouldn’t like but which was inevitable, placed ahead of her in life like an obstacle on a train track.

Umvonk finally voiced an answer.

“It is poetic because of your work.”

But that wasn’t enough. That wasn’t sufficient.

“No,” Galina interrupted. “There’s more to it, isn’t there? You told me the human race changed. What happened to humans?” she asked. There was a long silence.

“You are looking at one,” Umvonk said. Galina stepped back from the glass, stumbling, still staring at the whale’s huge eye as its flipper remained in place against the glass.

“No…” she said.

“Some of them migrated to a water world. They abandoned technology or technology abandoned them, and they remained stuck on the world.”

“It can’t be,” Galina said.

“They share your genetic code, Galina. Specifically, they are your direct descendants.”

“My son.”

“There is evidence that after your untimely death, your son devoted his life to the continuation of your mission. My people picked up records from Earth about it, indicating he was successful. I believe he is the direct progenitor of the species you see before you.”

“Are they intelligent?” Galina asked.

“Are you asking if they can recite stories and remember all of human progress?” Umvonk asked bluntly.

“Yes.”

“Then no, if that is how we are to define intelligence, then they are not intelligent by that standard. They are merely an endangered species on an aquatic world many lightyears from the rubble of Earth. Without this museum’s centuries-long mission to collect information from around the galaxy, nobody would know these creatures had anything to do with humans at all. Your species abandoned technology and storytelling not long after they abandoned dry land.”

Galina was insulted. She stepped back to the glass, pressing her face against its cold surface.

“But passing information on can happen in water,” Galina said. Umvonk frowned with seven of his face-tendrils.

“Of course, it can, but that is not what happened here,” he explained.

“No. I refuse to believe that. All that history can’t be gone. All that progress.”

“It is not gone. You are here now, and there were those who learned from the scrapheaps of the humans, those who reverse engineered your technology to make leaps through their own evolution. Your species played its part in a larger story,” Umvonk said gently. Galina tilted her skull, pressing her face as close as possible to the glass. Silently she wished to phase through it, to join the whales and drown among them.

Her voice faltered. “I never took my son to the aquarium. I always meant to, but we never had the time.” On the other side of the glass the grey whale rolled and twisted in the water, its eyes tracking Galina with intense fascination. Umvonk observed her pain but seemed to still be oblivious to it.

“I could check our records for any evidence your son went to that aquarium on Earth, if you wish.”

“No,” Galina said.

“Understood.”

There was a long silence, punctuated only by the dulled sound of tapping from the other side of the glass. Galina fell to her knees and wept as she watched the whale, as more of them congregated around the first and observed her. Umvonk collected his tendrils into something that looked like a concerned professor.

“They were here before us. We share a solar system. Strangely, there is no human activity registered on any of the other living worlds in this system, no genetic material. So, we presume the humans’ last refuge was this water world, that this was the final resting place of their knowledge and culture.”

Galina refused to accept this. She wiped the tears from her eyes and groggily stood up, observing the crowd of whales that had collected near the glass.

“Is there any way we can tell them, any way they could understand?”

“They lack the intellectual capacity,” Umvonk said. Galina Agafonov stretched and cracked her back for the first time in ten million years, marvelling at the creatures and the technology around her.

“But you could raise that. You could make them smarter.”

“We are not interventionists in that sense. We protect life, not alter it,” Umvonk explained. Galina shook her head and got thinking.

“Perhaps it was a survival technique. Domesticate themselves, hide from something?” she pondered. “Maybe they made life too easy and gradually threw parts of themselves away. They could come back, using your archives and all this knowledge. They could evolve back into humans. That’s happened with some animals before.”

Umvonk twisted his tendrils and barbs into something reminiscent of a large smiling face.

“Perhaps,” he humoured her.

END

So that’s the end of that. I do like the idea of writing more stories with Galina exploring the new universe she is reborn into, but I feel that part of the lore fits better in your imagination than it does on the page. So that’s it. I am leaving her alone for now. There is room to sneak her into the expanding universe, with the dreamscreen tech and the eons where humans are missing, but let’s not go there quite yet. Let’s judge this story on its own without turning its existence into a major spoiler for a novel I haven’t even told you all about…

So, what did you think?

Is there anything I could/should do to improve this story?

Did it end how you expected it to?

Should I release this as an audiobook?

Newsletter improvement time

Lastly, I want to ask you a question about the future of this newsletter. A large group of you are new subscribers this week, brought in from my free WBTH and Earthloop chapters. Many of you are cool people I met at ComicCon Manchester, which I will be talking about in a few days once I’ve collected my thoughts back together. I’d say hi to those whose names begin in L, J, and M, but I value your privacy a bit much for that. I’ll wait for you to say hi first.

You’re all here for free stories, obviously. That’s what the business card says, and that’s the promise I am sticking to.

I have recently joined Bookfunnel, which means I am finding a lot of free eBook/audiobook/sample giveaways by other authors. Here is an example.

I want to be able to share more of these things with you, but sometimes there is a lot of them, and I don’t want to spam your inbox.

So how should I share them?

A dedicated second newsletter. This would be opt-in, not a pre-included thing like my sometimes comedic News and Updates subletter, but a separate newsletter you have to sign up to manually.

Don’t share them here at all. If you pick this option, I won’t put them on substack at all. I’ll just blast them at twitter.

This option would see me trying to include them subtly at the end of my regular story and updates posts. So the Bookfunnel giveaway groups won’t get a specific post, but they will be included at the end of my posts.

Thanks for reading. I hope you enjoyed the story. If you did, or didn’t, please to let me know. I am enjoying this little community and it is very inspiring to see people getting excited about what happens next in the weird multiverse inside my head. I’m a big fan of this story, and whilst I wish it was in WBTH1, it might show up in WBTH2 (yes, that is happening one day).

Here are two more links for bookfunnel, as a trial run of option 3. I have joined a comedy sci-fi author swap with SC Jensen and DM Pruden.

Thanks for being here. If you have any suggestions for me, please let me know!

Stay innovative

-Phillip

Hummm, based on what I know of NORMAL human psychology I'm fairly certain that suicide is what the last human would eventually do because there's nothing to live for.

I vote for an audiobook.