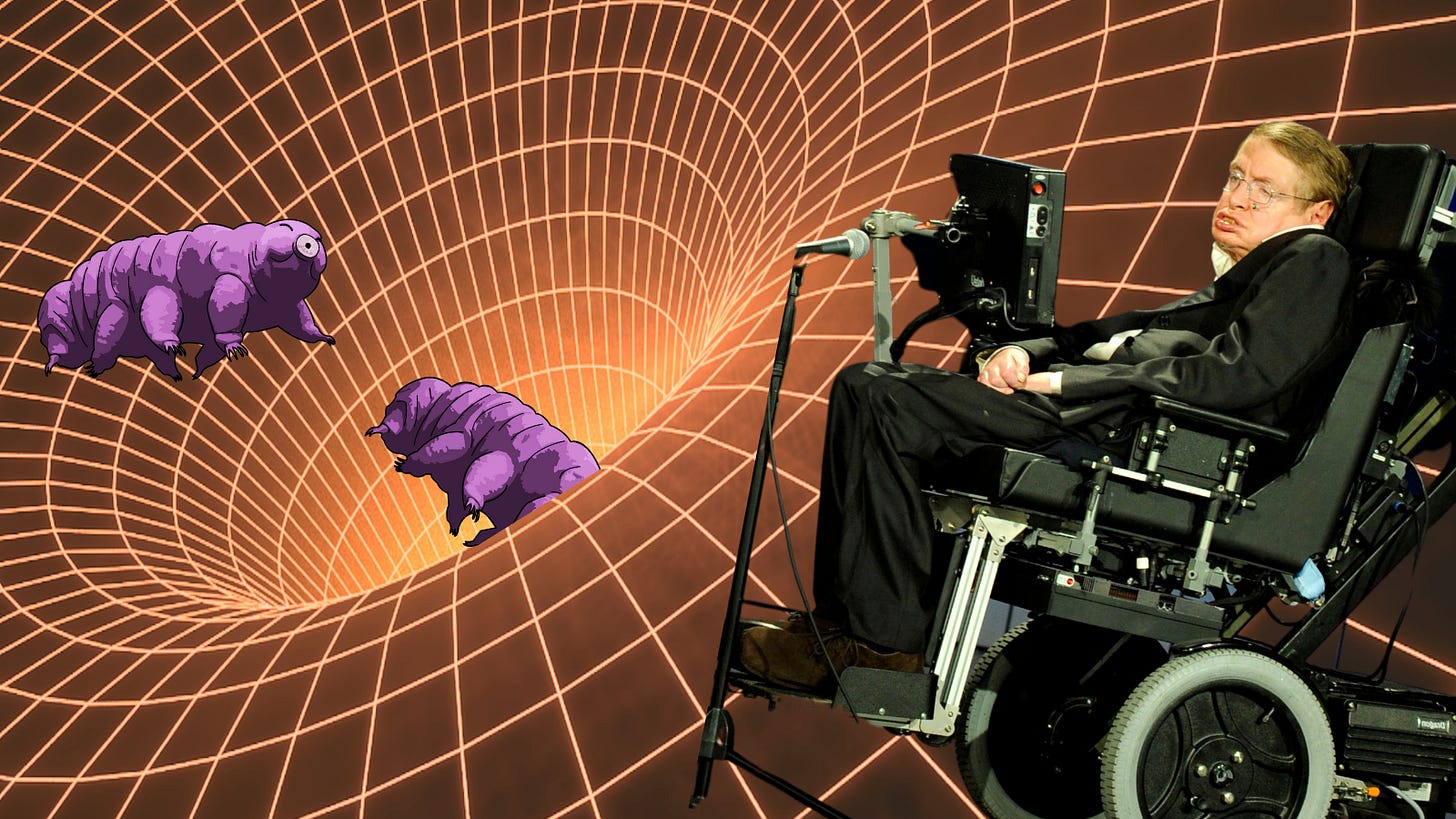

Tardigrade - A short story

Including Stephen Hawking and a very sneaky nod to a larger universe.

So, as you all know, I’m writing a new book called SEVEN STORIES ABOUT TIME TRAVEL1. To celebrate that, I will be doing a few fun promotional things soon. This is one of them, I’m posting an early draft of this story for free.

Interesting stuff: In this story, Stephen Hawking’s party for time travellers, including its date and invitation card, are completely real. Everything else probably isn’t.

TARDIGRADE

On June 28th, 2009, Professor Stephen Hawking hosted a party at the University of Cambridge with an exclusive guest list. He was not looking for a particular set of names to invite, but a particular type of person: Only time travellers from the future were allowed to attend.

Hawking enforced this rule with one simple trick; he sent out the invites long after the event had happened. Therefore, the only people who could learn about the party were people who existed after the event. Anyone existing before the event wouldn’t know about it, and anyone observing the goings-on inside Cambridge during the event would be blissfully unaware that one of humankind’s smartest, kindest minds was sat quietly in a brightly lit room at that precise moment, waiting with balloons and drinks, for travellers from the future.

Professor Hawking moved under a banner in the room which read,

WELCOME TIME TRAVELLERS

Upon the table were snacks and champagne. A film crew for the Discovery Channel was taking photos and filming, some of them no doubt half-expecting a traveller might show up. Everything was going according to plan. The invites were already printed, ready to be shown to the world after the event.

You are cordially invited

to a reception

for Time Travellers,

Hosted by

Professor Stephen Hawking

To be held at

The University of Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College

Trinity Street

Cambridge

Location: 52° 12’ 21” N, 0° 7’ 4.7” E

Time: 12:00 UT 06/28/2009

No RSVP required

The grandfather clock in the corner ticked its way to 12:00. The door did not budge. There was no knock. Another ten minutes. No knock. Another ten, then twenty, then thirty. The film crew stayed with Professor Hawking, but even fellow professors or curious passers-by who may have caught wind of this secretive party before it was held, neglected to show up. The champagne grew warm as the universe tried to balance its energy with the rest of the room. Most of the food went uneaten. The balloons began to deflate, slowly but surely. Professor Hawking had waited over an hour for nothing.

Eventually the human race carried on. This unusual experiment was remembered for a few centuries, but after a while its memory faded. What Professor Hawking and the film crew didn’t know was that a time traveller had indeed arrived, but, due to unforeseen circumstances beyond their control, they were rendered incapable of making their existence known.

Time-holes were hard to maintain. For macroscopic objects to pass through a tremendous amount of energy had to be expended on a hole. One easy way of minimising this energy requirement was to make the hole smaller. It was after all a tear in normal spacetime, a wound which required constant energy to maintain. The bigger you made one, the more energy it needed. Conveniently, the largest time-hole possible for future humans was only slightly bigger than a tardigrade.

And so, in it went.

But tardigrades cannot read English, nor can they communicate meaningfully with giant physicists. Even if they could, they make terrible conversation and only ever speak of sex and algae, like that weird vegan poet who works in town and smells suspiciously like fried chicken.

So, the tardigrade got an upgrade.

It became an upgradigrade.[1]

The upgradigrade was treated to a precarious operation that opened up its insides and placed a very small, very sensitive microchip inside its hemocoel. That’s the bit where it’s veins, lungs, and heart(s) would be if it needed or indeed wanted any, but it didn’t. A tardigrade is small enough to wiggle its nutrients around without those otherwise important transport hubs. It would be an ideal drug mule if it were only a few hundred times bigger. Nutrients get around its anus, stomach, oesophagus, nervous system, and brain[2] just fine without needing tubes.

The microchip would absorb and save information about its environment and, if possible, open up a line of communication with a nearby mobile phone, so as to text Professor Stephen Hawking or someone else in the room to say, “Hello, we managed time travel, but it only works for tiny animals!”

The upgradigrade was prepared at the tip of a needle, where an insomniac scientist-sculptor had crafted it a tiny chair on one of their days off, then ushered gently into a state of cryobiosis like an elderly relative. It shed ninety seven percent of its water, ushering in what might be the worst, tiniest hangover in history. Now entering its ‘tun state,’ the tiny creature began creating its own antioxidants. This was not a feature of the human-made upgrade. Tardigrades already did this, which made them perfect candidates for travelling across a warped spacetime which was liable to snap and release immense bolts of radiation at any second. The antioxidants provided a valued defence against the radiation.

The needle was pushed into the tiny time-hole and a tiny gust of air (sterilised, so as not to flood the year 2009 with future diseases such as the ‘moon wigglies’) was exerted from within. The upgradigrade left the future and began its journey into the past, much like a middle-aged man having a mental breakdown.

This journey was not instantaneous. Indeed, another reason it would be impossible for humans to make the trip was because it would take just as many years to get back through time as it took for the past to grow up into the future. As the tardigrade was sent from a date approximately one thousand years after 2009 (we lost a few years due to the wars on Jupiter) a time machine would also need to preserve its human occupant somehow, or even go as far as to become a generational starship for an entire tribe of travellers.

Simply put, it just wouldn’t work. The entirety of what remained of human civilisation simply did not have the resources or the energy to open a time-hole that large in space. The time part was arduous enough. A tardigrade was a perfect time traveller in every which way. He (this traveller was a male, not that it’s relevant) could survive the immense radiation storms of backward-leaning bendy spacetime. He could fit on the tip of a needle small enough to enter the tiny time-hole. He could freeze up and dry up and survive centuries without nutrients (this part was untested, but one had lasted a few decades in outer space in the 2100s, so it was worth believing, especially since this tardigrade was a direct descendant). And lastly, he could come back to life with as little as a few molecules of water, or champagne, if he landed right and Professor Hawking wasn’t in the way of his trajectory.

And so, the years began to pass, forward and backward and forward again. The human race of 2009 grew into the human race of 3000-something. The upgradigrade fell through time in the direction of a long away yesterday, each day taking a day to pass. To him, it hardly would have felt like time travel at all. He would almost die and come to life again at the other end of a strange and incomprehensible journey. For the upgradigrade tardigrade did not know nor care about his mission. All he knew was that he was hungry and wanted to eat and have sex and then sleep. In this way, he was perhaps more human than whatever weird freaks he had left behind in the future. But we aren’t talking about them today. We shall leave them behind in the future, where they belong.

The upgradigrade awoke inside a droplet of champagne from a recently opened bottle. He exited his ‘tun state’ gleefully, mooching around inside the droplet for a female. Too small to be drunk, the tardigrade instead pawed around in a sloppy stupor simply because that was how he lived his life, and who are we to judge?

The radiation from the time-hole quickly eroded the thing and it vanished, not that anyone would have noticed. Next, the tiny droplet of champagne arced toward the edge of Professor Hawking’s wheelchair. The upgradigrade tardigrade spiralled downward in his boozy starship. Both tardigrade and kindly human genius were blissfully unaware of each other’s presence. The droplet landed, barely missing the Professor’s suit. At this particular moment the upgradigrade was thinking about eating a nice bit of algae. He crawled sluggishly out of the remains of the droplet, operating now under the instruction in the microchip in his hemocoel in the same way you might operate under the instruction of the robot crabs that live in your bones, if there were robot crabs in your bones, which there aren’t[3].

The little upgradigrade tardigrade scurried (from his perspective) into a patch of air from which he could begin his broadcast. From here he might have seen the words on the banner in the room, the time on the grandfather clock, or the ingredients on the side of a champagne bottle. But he didn’t because he couldn’t read. The microchip began its tiny broadcast, looking for mobile phones in the room. But it didn’t find one. Something must have been blocking the system. The scientists had prepared for the radiation from the collapsing time-hole itself, but not for any spikes generated in the local area, or indeed a closure of local phone networks. Perhaps it was the architecture of the building, a heavy cloud, or a disgruntled anti-paradox tardigrade crew in black suits and sunglasses, but something was stopping the upgradigrade from communicating.

But it was fine for the tardigrade, as he had no idea what was going on anyway. He didn’t care. He was hungry, and horny. The microchip kept pushing on with its signal, but nothing useful happened.

Later, the upgradigrade tardigrade would stumble upon a female of his species and attempt to procreate with her, engaging in tiny foreplay and watching as she seductively detached her previous skin layer (between which and her new skin she would place her eggs for him). At this point they would get close, and he would ejaculate onto the eggs. Later still they would fall asleep together. He would smoke a tiny but imaginary tardigrade cigarette and she would think about the last man she had round. Later still, when our time travelling upgradigrade friend had left without leaving his details, the female tardigrade would discover that his sperm was worthless. His genetic material would die with him, just as the scientists intended before they sent him on his way. He lived a happy life going around pretending to reproduce with strange women from the uncivilised past of tardigrade culture, because tardigrades develop a culture in about a thousand years or so, they just don’t tell humans about it (because why would they? We are basically weird-shaped planetoids that speak so loudly we shake the viscous atmosphere around the tardigrades even when we whisper. We are cosmic horrors, freakish, endless things which lollop around and stage horrid alien abductions of tardigrades only to stick strange machines in them and throw them through irradiated time-holes. Even if they could speak to us, they’d be too scared.

Anyway, the party went on without the little tardigrade time traveller, and the universe carried on as usual. Meanwhile, outside Gonville and Caius College in Cambridge, various shapes and styles and sizes of time travellers appeared and disappeared, each with differing opinions on whether or not they should intervene with this party at all. Each erasing the last from spacetime before being erased themselves by the next, or the previous, or the adjacent traveller. It gets complicated. Travellers and antitravellers smashed into each other outside, time machines warred in private psychic battles with ancient artificial minds. A man was beaten half to death in a nearby toilet just because he looked like a time traveller, but he was just wearing silly shoes. Unknown gods and horrors were unleashed, laser beams streaked across the skies, the sun was extinguished and relit, and nobody noticed because it all happened so quickly that it barely happened at all.

And then you read this story and heard all about it, which is a shame, because people aren’t supposed to know. You had a good life.

[1] Oh, you think that name is bad do you. Well, I didn’t name it, the fictional public in the fictional future of this very real story named it. It had nothing to do with me. The public are idiots. It doesn’t matter if they’re from the future or if they’re fictional, they don’t get any smarter. Only the smart people get smarter. The average people cannot possibly become more average. That’s the rules.

Just be glad it didn’t also have digitigrade legs. Imagine the name then.

A digitigradeupgradigrade.

They do have backwards facing back legs, however. Bet you didn’t expect tardigrade facts in the footnotes of a Time Travel book, but here we are. I hope you enjoyed them.

[2] Interestingly, humans also contain those parts, and many would presume that list was written in order of importance. Tardigrades may see us as showing off, having our lungs and veins and all.

[3] Don’t believe him. The crabs are in there. Listen to their tiny claws clamping together.

Please do let me know what you think of this one. This is an early draft, so it needs a bit of a beating.

EDIT: It has since recieved the beating, but feedback is still valuable as the book is not yet out.

Loved the story. Back to the now 23,273 unread emails.

Quite funny. Thank you very much!